What you need to know about parvovirus in dogs

Get all your puppy parvovirus questions answered here!

Good Dog is on a mission to educate the public, support dog breeders, and promote canine health so we can give our dogs the world they deserve.

Good Dog is on a mission to educate the public, support dog breeders, and promote canine health so we can give our dogs the world they deserve.

Good Dog is on a mission to educate the public, support dog breeders, and promote canine health so we can give our dogs the world they deserve.

Join our Good Breeder community

Are you a responsible breeder? We'd love to recognize you. Connect directly with informed buyers, get access to free benefits, and more.

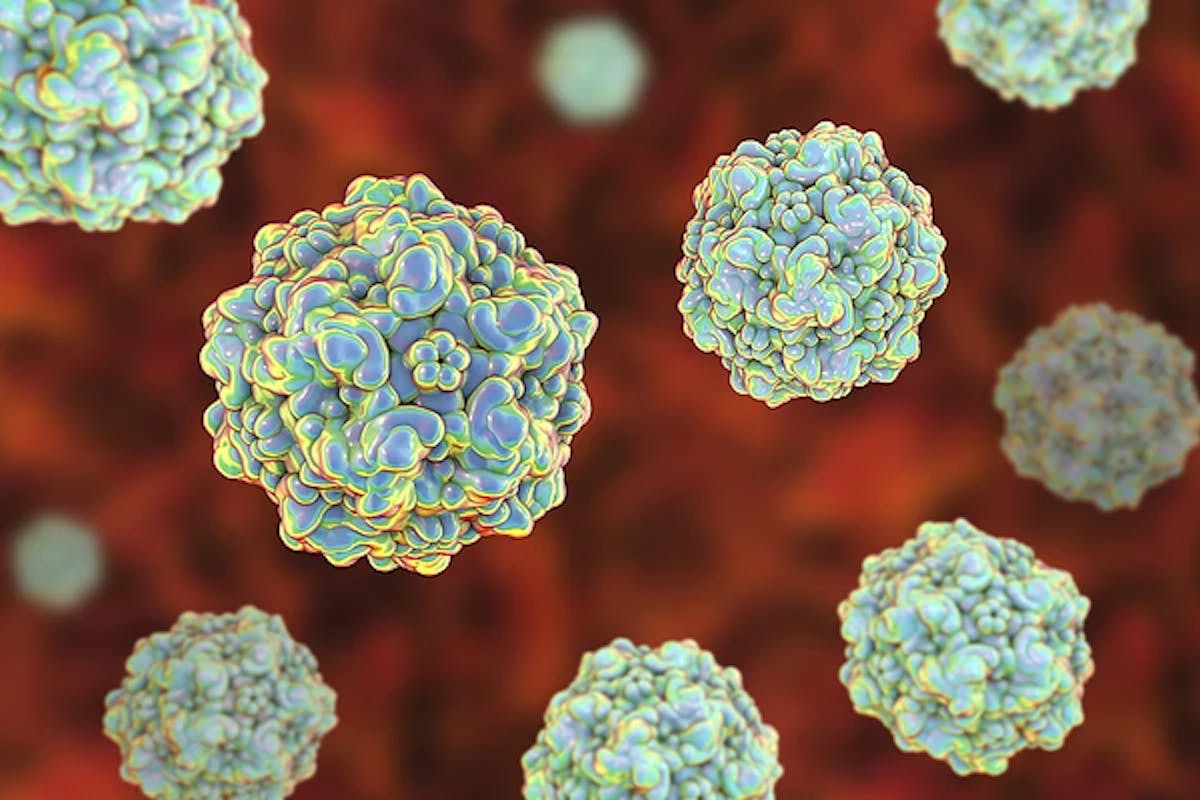

What is parvovirus (parvo)?

Canine parvovirus is an extremely contagious and potentially deadly disease generally affecting the gastrointestinal tract of young dogs. The virus (canine parvovirus type 2) is thought to have originated in the 1970s either from a related wild carnivorous ancestor or due to a mutation from a similar virus in cats (Feline panleukopenia virus, FPV). Since its emergence, multiple strains/variants have been identified, with a variety of wildlife (wolves, coyotes, foxes, racoons, skunks, etc.) also susceptible to infection.

How do dogs get parvo?

Canine parvovirus is transmitted directly (eating infected stool) and/or indirectly (an inanimate object contaminated with infected feces coming into contact with the nose or mouth) to susceptible animals. The susceptibility of the dog depends on their immune status and how much virus they are exposed to. The virus spreads from the mucous membranes of the mouth and nose to the lymphatic system and into the bloodstream. The virus can then be shed in feces as early as 3 days after exposure, and as long as 3-4 weeks after exposure. Canine parvovirus is unique in its hardiness, surviving for months in the right environmental conditions and being resistant to heat, cold, humidity, drying, and a wide array of disinfectants.

What are the signs of canine parvovirus?

Once a susceptible dog is exposed to the virus and becomes infected, clinical signs will usually begin 3-7 days later. The hallmark symptoms are severe vomiting and diarrhea (which often has a strong smell and may contain blood), but can also include lethargy, depression, lack of appetite, and fever. It is critical to have the dog examined by a veterinarian at the onset of any symptoms. Vomiting and diarrhea can rapidly dehydrate a small puppy and complicate treatment.

Diagnosing the disease can be challenging due to the generic clinical signs. But if canine parvovirus is suspected, a test to confirm presence of the virus or virus antigen in feces is required. Additional tests, including blood work may be needed and recommended by your veterinarian.

How is parvovirus treated?

If infection is suspected, therapy revolves around supportive care and managing clinical signs as there is no treatment to kill the virus. The damage to the intestines and blood cell elements can result in dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, and infection in the bloodstream. While different for every patient, treatment plans usually include hospitalization with intravenous fluid therapy. Additional recommendations may include nutritional supplementation, antibiotics, medications for nausea/diarrhea/pain control, and even blood transfusions. Most patients respond to medical therapy and recover appropriately if aggressive therapy is implemented promptly. These animals then retain lifelong immunity against the specific strain of parvovirus they were infected with.

Prevention necessitates proper vaccination as the passive immunity acquired from the mother’s colostrum is only present for a limited period of time. If maternal antibodies are above a certain level at the time of vaccination, they can actually neutralize the vaccine. Therefore it is important to vaccinate in a series, in an attempt to administer the vaccine as close to the time that the mother’s antibodies are no longer effective. The initial series of parvovirus vaccinations (included in combination vaccine) should begin at 6-8 weeks of age, with subsequent administrations every 3-4 weeks after until the puppy is 16 weeks of age. During this period, it is critical to keep puppies away from possibly contaminated areas (such as dog parks, pet stores, etc.) and animals of unknown health/vaccine status. Following this series, boosters should be given on a regular basis.

In addition to vaccination, practicing proper hygiene and implementing preventative measures are important. Cleaning indoor areas/objects with diluted bleach (1:30) can inactivate the virus and diluting outdoor areas with water can decrease the concentration of the virus over time. Removing waste as quickly and hygienically as possible is critical. Possibly infected animals should be isolated.

Sources:

Goddard, Amelia, and Andrew L. Leisewitz. "Canine parvovirus." Veterinary Clinics: Small Animal Practice 40.6 (2010): 1041-1053.

“Canine Parvovirus.” Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, 25 Jan. 2021, www.vet.cornell.edu/departments-centers-and-institutes/baker-institute/our-research/animal-health-articles-and-helpful-links/canine-parvovirus.

Further resources:

Join our Good Breeder community

Are you a responsible breeder? We'd love to recognize you. Connect directly with informed buyers, get access to free benefits, and more.

.jpg?type=dog&crop=48x48)

-.jpg?type=dog&crop=48x48)