Modes of inheritance and your dog breeding program

Learn more about how traits are inherited and how it impacts dog breeding decisions

Good Dog is on a mission to educate the public, support dog breeders, and promote canine health so we can give our dogs the world they deserve.

Good Dog is on a mission to educate the public, support dog breeders, and promote canine health so we can give our dogs the world they deserve.

Good Dog is on a mission to educate the public, support dog breeders, and promote canine health so we can give our dogs the world they deserve.

by Dr. Mikel Delgado, PhD

Thanks to advances in genetics and canine health, breeders have more power than ever to make informed decisions that can control and reduce the risk of producing dogs with harmful health conditions in future generations. Let’s take a look at how harmful conditions may be inherited, and how to use genetic testing in your breeding program.

The most common ways dogs inherit a condition or trait

You will often hear reference to “modes of inheritance” - this just means how an animal inherits something from their parents. At each location on a gene, an individual inherits two copies of an allele -- one from each parent. Whether or not that condition or trait is expressed depends on how it is inherited.

Most conditions follow one of just a few modes of inheritance, the most common being:

Autosomal dominant: An individual only needs to inherit ONE copy of the allele to be affected, and they may inherit it from either parent. Dogs with harmful conditions that are inherited in this manner should not be bred.

Autosomal recessive: An individual needs to inherit two identical alleles (mutations) to be affected. When this happens, it is often because both parents are carriers of the condition.

Sex-linked disorders: are conditions that are carried by the X chromosome.

X-linked dominant: refers to conditions that are associated with genes on the X sex chromosome. Males have one X chromosome and females have two X chromosomes. A dominant trait or condition only requires one copy of the allele, meaning that all males with the variant will have the condition. Because the trait is dominant, females with one copy of the allele will also have the condition.

X-linked recessive: refers to conditions that are associated with genes on the X sex chromosome. Males have one X chromosome and females have two X chromosomes. Because males only have one X chromosome, if they inherit a copy of the harmful mutation, there’s no “healthy” allele to protect them. They will inherit the condition. Females have a better chance of avoiding the condition because they would need to inherit two copies of the mutation to be affected. The extra X chromosome offers females a bit of extra protection in the case of x-linked recessive disorders.

Incomplete penetrance: Sometimes having a mutation is not a guarantee that the condition will be expressed. Penetrance can vary, meaning in some cases, most dogs with the mutation WILL develop the disease, but in other cases, very few may.

Incomplete dominance: is when neither allele determines a trait, but instead they have a combined effect. An example would be the gene for a curly coat in dogs. Dogs with both curly alleles have a tightly curled coat; dogs with both straight alleles have a straight coat. Dogs with one of each allele have a wavy coat, which may vary in waviness from dog to dog.

The problem with recessive conditions

Recessive conditions can be tricky because dogs with a single copy of a mutation may not have any signs or symptoms of the disease. This is also the most common mode of inheritance for disease.

Dogs with one copy of the mutation are known as “carriers” - they carry the allele for the trait, and most importantly, they may pass on those alleles to their offspring. When mated with another carrier, it is highly likely that 25% of their offspring will be affected (have the condition). For some mutations, this can be lethal or ethically problematic due to the nature of some illnesses.

Affected dogs will contribute one copy of the recessive allele to all of their offspring.

A clear dog does not carry the mutation and will not pass on a mutation to offspring. However, dogs are only cleared for the genes they are tested for. They may carry mutations that have not yet been identified

Carrier dogs should not necessarily be removed from a gene pool, as long as they are ONLY bred with dogs who are known to be clear. However, including too many carriers in a breeding population increases the likelihood that the affected population will increase, and the allele will become more prevalent. There is a balance between eliminating all risk of passing on alleles and limiting the gene pool, which reduces genetic diversity and may lead to other problems.

The most important thing to do is test all of your dogs before breeding, and if you are selling puppies that may be bred, they should also be tested before mating.

Dog breeding matches and risk of outcomes with autosomal recessive conditions

Green - GO - a safe breeding match

Yellow - generally safe, but carriers will be maintained/increased in the population

Orange - caution - risky because there is a high chance that affected dogs will be created

Red - STOP - all puppies will be affected

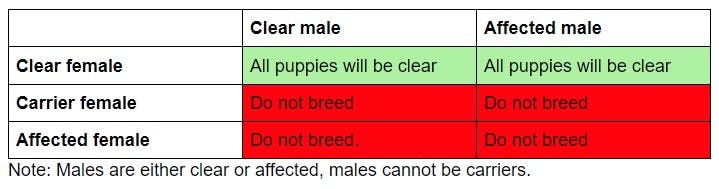

Dog breeding matches and risk of outcomes with X-linked recessive conditions

Why it matters for your dogs

The goal of a solid, ethical breeding program is to maintain or improve the numbers of clear dogs in a population. Breeders should use the available tools to prevent an increase in affected dogs, and to limit the number of carriers, while maintaining genetic diversity within a breeding population.

If you need assistance making breeding decisions based on genetic test results, many testing companies and universities provide genetic counseling services.

References

Ackerman, L. (2021). Modes of Inheritance.Pet-Specific Care for the Veterinary Team, 137. Accessed at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9781119540687#page=143

Join our Good Breeder community

Are you a responsible breeder? We'd love to recognize you. Connect directly with informed buyers, get access to free benefits, and more.

.jpg?type=dog&crop=48x48)

-.jpg?type=dog&crop=48x48)