Portosystemic shunts (liver shunts)

A potentially dangerous condition that can lead to liver damage in your dog

By Dr. Mikel Maria Delgado, PhD

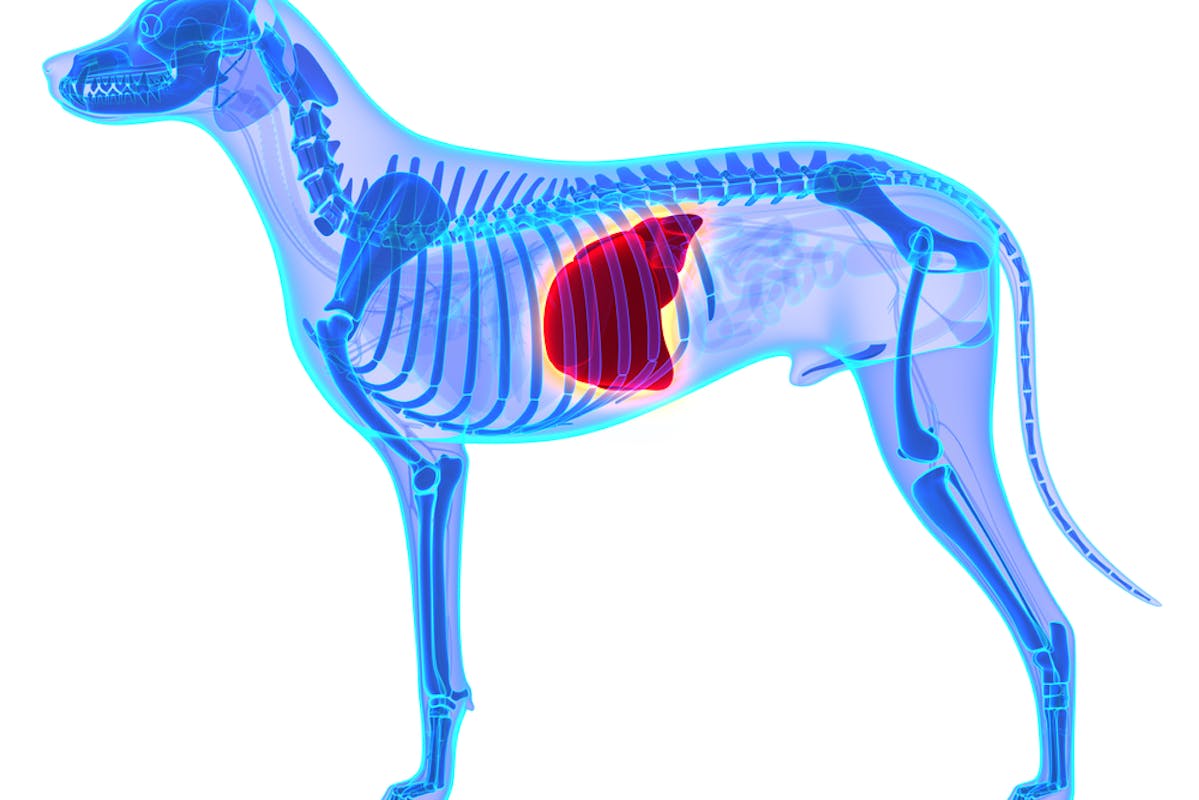

Portosystemic shunts, also known as liver shunts, are caused by abnormal development of blood vessels between the gastrointestinal system and the liver. Normally, blood flows from the gastrointestinal system, including the pancreas and the spleen, to the liver. During this process, the liver filters out toxins, extracts nutrients from food, and then sends the blood on it’s way back into the bloodstream. When a dog has liver shunts, the blood by-passes the liver, circulating into the bloodstream without filtration.

How do dogs get liver shunts?

There are two types of liver shunts: congenital (meaning present at birth), and acquired.

Congenital liver shunts are generally considered a birth defect or a genetic predisposition related to the abnormal development of blood vessels. This is by far more common, affecting about 80% of dogs with liver shunts. There are two types of congenital liver shunts: extrahepatic, when abnormal blood vessels are located outside the liver, and intrahepatic, when abnormal blood vessels are located inside the liver. Small and toy dogs are more likely to be affected by extrahepatic shunts, and larger dogs are more susceptible to intrahepatic shunts. Dogs with congenital liver shunts typically have signs by three years of age.

Acquired liver shunts tend to show up later in a dog’s life, usually as a result of another medical condition, such as high blood pressure or cirrhosis of the liver.

Signs of liver shunts

Some of the more common signs of liver shunts include stunted growth or being the runt of a litter, along with seizures and other neurological signs such as disorientation, head pressing, or staring into space. Some dogs may have signs such as vomiting/diarrhea with blood, bladder stones, or other urinary difficulties. Some dogs will develop kidney or bladder problems later in life.

Diagnosis of liver shunts

Tests for liver shunts include bloodwork and urinalysis. Your veterinarian may perform a specialized blood test for bile acid levels to assess liver function, as most dogs with liver shunts also have elevated bile acid levels. Imaging such as x-rays, CT scans, or ultrasound are often used to diagnose liver shunts.

Treatment and prognosis for liver shunts

Some dogs can be treated with a therapeutic, low-protein diet and medications that reduce absorption of ammonia. Antibiotics and lactulose are often given; as a result:

- the pH of the intestinal content is lowered

- absorption of ammonia is decreased

- feces are moved through the digestive tract more quickly

- the overall bacterial population in the gut is decreased.

Many dogs can be managed well on medication and dietary changes, but unfortunately nearly half of these medically managed dogs will succumb to their disease within 10 months of the diagnosis due to the neurological effects and liver damage caused by the shunt.

For some dogs, surgical correction of the shunt is a viable option. The best candidates for surgery are smaller breed dogs with a congenital shunt, dogs with just one abnormal vessel, and dogs with extrahepatic shunts.

Breeds commonly affected

Small breeds that often experience liver shunts include Yorkshire Terriers, Maltese, Shih Tzus, Dandie Dinmont Terriers, Schnauzers, and Cairn Terriers. Liver shunts are also seen in larger dogs, such as Irish Wolfhounds, Old English Sheepdogs and Labrador Retrievers.

Genetic influences and breeding decisions

There is currently no genetic test for liver shunts, although scientists in the Netherlands have been conducting research with the goal of identifying related genetic mutations that would allow for the development of a genetic test.

Liver shunts may be related to a genetic predisposition, although the mode of inheritance is at this time unclear. Breeders should consider pedigree, overall genetic diversity, and the presence of puppies with liver shunts coming out of their program to make the best breeding decisions moving forward.

Resources

VCA: Portosystemic Shunt in Dogs

American College of Veterinary Surgeons: Portosystemic Shunts

Tufts: Clinical Nutrition Services: Feeding Pets with Liver Shunts

Veterinary Information Network: Exploring the Mysteries of Liver Shunts

O'Leary, C. A., Parslow, A., Malik, R., Hunt, G. B., Hurford, R. I., Tisdall, P. L. C., & Duffy, D. L. (2014). The inheritance of extra‐hepatic portosystemic shunts and elevated bile acid concentrations in Maltese dogs. Journal of small animal practice, 55(1), 14-21.

Van Steenbeek, F. G., Leegwater, P. A. J., Van Sluijs, F. J., Heuven, H. C. M., & Rothuizen, J. (2009). Evidence of inheritance of intrahepatic portosystemic shunts in Irish Wolfhounds. Journal of veterinary internal medicine, 23(4), 950-952.

Join our Good Breeder community

Are you a responsible breeder? We'd love to recognize you. Connect directly with informed buyers, get access to free benefits, and more.

.jpg?type=dog&crop=48x48)

-.jpg?type=dog&crop=48x48)